In the years following the Great Depression, a student who would not be returning to college stopped by to thank his favorite professor.

“Sonny,” the professor said. “You’re leaving a place which specializes in knowledge. Do you remember what I told you all on the first day I saw you?”

“Yes sir,” Sonny said. “You told us that a man with no wisdom is a fool. And if he stayed that way, college could only turn him into a D—- fool.”

“That all you need to remember,” the professor said. “One thinking he has great knowledge is never wise. Carl Linnaeus would be ashamed of them.” He paused. “Do you remember Linnaeus?”

“No, sir.”

“He was the man who gave humans the name ‘homo sapiens: man walking, upright, and possessing wisdom.’”

“The first part is easy,” he continued, “unless you have a physical affliction. But ‘becoming able to discern and judge wisely’ is not. Everyone can gaze, but few can discern. Looking requires no effort, but seeing is intense work.”

“I want to tell you a story,” the professor said. “ Around 100 AD, a man named Cai Lun noticed that all the laws and the private records in China were written on silk. That was much better than the rocks, wood and leather that their forefathers used, but silk was too expensive for most people to afford.”

“I bet the farmer wrote on his britches leg,” Sonny said.

“He may have,” the professor smiled. “But one winter, Cai noticed a wasp nest hanging from a tree. He went outside, knocked it down with a bamboo pole, then brought it in to take a look.

“After he cut the nest in two, he found the walls were made of a thin grey material. If paper had been invented then, Cai would have said this material looked like paper, like pages from a book. Those pages make me think Cai cut open a hornet’s nest.”

The professor paused. “If he could make sheets like the ones the wasps made, he could use them to replace silk as a writing surface. To find out how the wasps built a nest, Cai waited for spring. Then he found a red wasp nest on the side of his workshop. Cai watched it fly to the bamboo scrap pile, then followed. He got close enough to see it working a section of bamboo reed which was leaning against a tree.

“The wasp worked from top to bottom. When it flew away, Cai walked over to examine the surface of the reed. There he saw a light colored stripe in exactly the same place where the wasp had been working. The bamboo wood looked grey everywhere but on that toothpick-sized stripe. The wasp that chewed grey wood made a grey nest.”

“Cai walked back to examine the nest, getting close enough to see the wasp moving. Over time the honeycomb wall grew taller. Cai reasoned that the hornet must be chewing up the bamboo wood, storing the paste in its cheeks, then flying to the construction site, where it squeezed out the paste onto the wall, using its front feet to assist.

“Then, Cai saw hornets sitting at the mouth of a nearly completed nest. He found if he squinted his eyes, he could see the tiny insects more clearly; that’s how he saw one wasp flying in place over the paste, moving its wings so fast that they became a blur.”

“He was drying it,” Sonny said.

“Exactly,” the professor said. “Fanning the wet wood paste to dry it quicker, to harden into something like papier mache.” The professor paused. “At this point Cai had observed the entire process. How do you think he remembered all the steps?”

“He needed a piece of silk,” Sonny smiled, “to write them down.”

“Exactly,” the professor chuckled. “From what I have told you, what would you write?”

“The hornet chewed on a piece of bamboo,” Sonny said, as the professor nodded at each step.

“It seemed to carry it in its mouth.”

“At the nest, it spit out the paste, then seemed to help form it with its front feet.

“Some wasps dry their paste by fanning it.”

“Good work,” the professor smiled.

Then he continued, “To take the place of the chewing, Cai beat the bamboo into a pulp. But he did not like the consistency of the watered-down paste, so he reasoned that wasp saliva must also eat up the pulp, leaving clean wood fibers. So he made lye from water and wood ashes, added it to the water in a large vat, then boiled the mixture until the heat and the lye water digested the pulp, leaving the fibers clean enough to make paper.

“Then he dipped the fibers onto a flat surface that would let the water drain through, and left them to dry. But when he tried to pick up his paper, it crumbled away. Wasp saliva must have had glue in it as well.”

“So Cai tried several recipes for glue before he settled on a tea he made from birch leaves. When he added it to the water, the finished paper did not crumble.

“Now that Cai had copied the wasps’ process, he was able to make what has been called the earliest sheet of quality writing paper. So, when Cai Lun demonstrated his invention in 105 AD, the emperor thanked him profusely, then gave him an exalted place in Chinese society, as well as much money. The emperor considered Cai to be a very wise man.” The professor paused again.

“You’re leaving tomorrow?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Thanksgiving is just days away, Sonny,” the professor said. “You will be home then, so we may never have another opportunity to speak this way.

“So let me leave you with this,” he continued. “A wise man will thank both his teacher and his teacher’s teacher. If this is true, I want you to consider how Cai Lun might prove himself wise.”

Sonny thanked his teacher, then said goodbye. On the way home, he considered his professor’s words until he discerned that he had more work to do.

On our national day to give thanks, I’d like us all to consider that question.

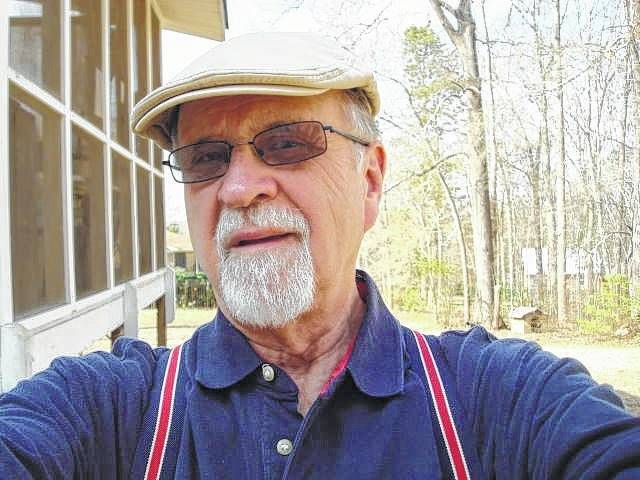

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.