“What color am I?” I asked my mother, as I inspected the eight crayons in my Crayola box.

“White,” she answered, as she mixed up tea cakes. “You’re white.”

I tried that color in my coloring book, but it didn’t look right; the face of the bronc-rider would have looked better in color-book beige, than in pale white. I looked at my hands; they were not white. And there was not a single color in that eight-crayon set that looked at all like mine.

“Why do they call us white, Mama?

“That’s just what we’ve always been called,” she said. “I don’t know why.”

Some years later, Binney & Smith offered a color called “flesh,” but it did not look like the color I saw in the mirror. I never liked the sound of that word, or the color of that crayon. And today I understand how it would have made Hank and Emory feel sad, because “flesh” was not at all the color they saw in the mirror. And the black did not fit them either, no matter how lightly you colored, but neither did the brown. So what color are we? I’m trying to find out.

When Daddy took us wading in Lanes Creek, I saw that he had two colors. Riding there, he let my sisters and me wear our “bathing suits,” but Daddy wore a shirt and pants, because grown men dressed like that unless they were at the creek or Cheraw Beach. In the car, Daddy’s face, neck, and hands were a deep brown color, suntanned over suntans from years of working outdoors. But there wasn’t a crayon to fit that color either.

When he threw his shirt onto the seat of the ‘40 Ford, I realized he was pale where his shirt sleeves kept the sun off his arms. He was pale white on his chest too, except for the brown “V” where his collar opened. When he took off his tan work pants and shoes, his legs and feet were pale white too — almost the shade of the white Crayola, but not quite.

A Sunday school song listed people-colors:

“…Red and yellow, black and white,

they are precious in his sight,

Jesus loves the little children of the world.”

But just as I had never seen a white person, or a black person, I had never seen a red person either. The only picture I remember of one was the booger boy on the Red Devil lye box. On the tobacco pouch the big boys chewed out of, the Red Man wasn’t red. Neither were the real live Indians we saw in Cherokee.

When I finally saw some “yellow” persons, I knew yellow wasn’t their crayon, either.

“They don’t have slanted eyes, either,” Daddy said. “Their eyelids are smooth and their eyes are level.” Daddy paused. “Some Oriental people have big eyes, some have little ones, some have big noses, some have little ones, some have thick lips, and big ears, and others have thin lips and little ears,” he said. “Just like everybody else.”

Daddy thought a minute, “So every person in the world looks different from everybody else.”

“Every single one?”

“That’s right. How would you recognize them, if everybody looked alike?”

“What about twins?” I asked.

“One set we knew,” he answered. “were so much alike, nobody could tell them apart … but their mother. She noticed one had a freckle on her ear.”

In 1992, nearly 40 years after I gave up crayons and coloring books, Binney & Smith introduced Crayolas in skin tones more like the ones we see on actual people. The colors were apricot, black, burnt sienna, mahogany, peach, sepia, tan, and white. For coloring books, these crayons surely did a wonderful job — but not for real people. One little child, running of crayons as he drew his own picture, voiced his frustration with, “God must have a whole lot of crayons.”

In 1969, writer Malcom Muggeridge travelled to India with a BBC film crew to speak with Mother (now Saint) Teresa, whose mission was to serve the unloved and unwanted in the slums of Calcutta. Muggeridge had become fascinated with the joy she and her nuns showed in their work.

Cinematographer Ken McMillan shot the footage in black and white, on Kodak 16mm motion picture film. In most of Mother Teresa’s houses, there was just enough light to expose the film. But in one house, the Home of the Dying, McMillan’s light meter barely read at all.

“There’s just not enough light,” he said. “It’s dark inside, and there is only one small window. “

“My gut says these scenes are our movie,” Muggeridge said.

“All right,” said the cinematographer. “But don’t be upset if the images are too dark to use.”

So they set up inside the house, McMillan rolled the camera, capturing Mother Teresa and the nuns, as Muggeridge spoke with them and showed them at work. Afterward, the crew shot some scenes outside the building in case the interior scenes were too dark. After the five-day shoot, McMillan, Muggeridge and producer Peter Chafer took the film back to London to be processed. They got their first look at the footage in a projection room at Ealing Studios.

“Don’t expect too much,” McMillan cautioned, just before time for the troublesome footage. He wanted to turn his face away, but when the scenes came up, they were lighted almost as well as if they had been shot outside at midday.

“That’s amazing!” he exclaimed. “It’s got to be that new Kodak film,” he thought to himself. But as he tried to give Kodak the credit, Muggeridge stopped him.

“It’s divine light,” Muggeridge gasped. “It’s from Mother Teresa … You’ll find that’s divine light.”

Divine or not, there was no doubt that the scenes were technically acceptable. Such was not the case with the additional footage they had shot in India, outside at midday, which was too dark to use. After that, a test of the same film stock, shot in England, showed the same disappointing results.

For the rest of his life Malcolm Muggeridge maintained that the scenes inside the Home of the Dying had been exposed by love from Mother Teresa, and that the BBC camera had filmed its radiance. Although he called the event a “photographic miracle,” Producer Peter Chafer never claimed such, saying, “I am no authority on miracles, but suspect that in this case they rest, like beauty, in the eye of the beholder.”

Although “Something Beautiful for God ”on BBC TV drew Mother Teresa’s work to the attention of the world, the “photographic miracle” was rejected by those who took issue with Muggeridge, and by others who agreed that Mother Teresa was a “lying, thieving, Albanian dwarf.” But because there is considerable evidence that something unusual is shown in the film, I believe fairness demands we consider the questions this evidence presents.

Could it be that all of us are of two colors: one which reflects the color of the skin we were born with — the ones called “red, yellow, black, and white” — and another, the color which radiates from our inner beings?

Might this radiated color explain why I could never find a Crayon to match human skin?

And most importantly, if we have two colors, “What color do I radiate?”

That’s the one that matters.

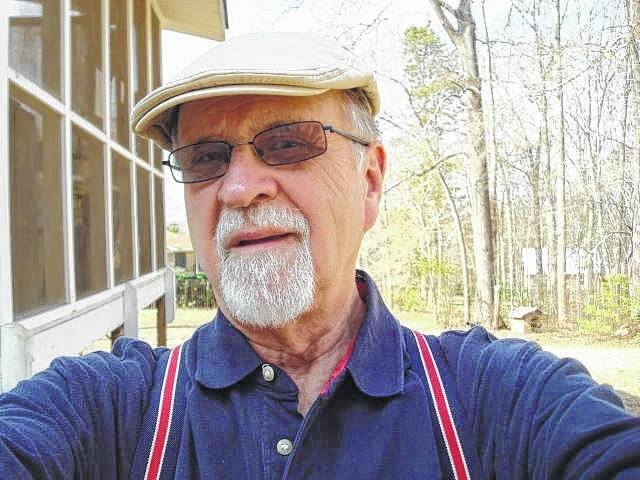

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.