Now don’t get me wrong, I am not ashamed of the way I sound — though I have had times when I was tempted to accept the shame from those who declare “You talk funny.”

That reminds me of a story. Blessed old Pete Seeger, the Yankee who did more for the 5-string banjo than anyone before Earl Scruggs, inherited his affinity for things Southern from his father. It is told that Charles Seeger came south intending to bring the music of the Renaissance Drawing Room to the common folk of Dixie. He wanted to teach us in order to lift us up. But Seeger was not a carpet-bagger, he listened and observed and learned that working Southerners had a music of their own. Not Bach, Beethoven or Brahms, but the words of common folk — the farmer, the mill worker and the railroad man — turned into song. He went back home to raise a family and teach them about this new and wonderful music, so that many of them came south to absorb it. His son, Pete, came to Asheville in 1936 to hear Samantha Baumgartner playing the 5-string the way it had been played when it was still a four string, with three long ones and that pesky short one. He appreciated the South, and loved its banjo.

Others are not so kind, especially when our speech is concerned. In 1962, a prep school graduate breezing through a calculus class at Chapel Hill heard my authentic Southern speech and promptly named me “Grit.” It was not a name given in appreciation of my dialect. Speaking of grit, it was only a few years later, when I made my first trip to a land where the plural of that term was disdained at breakfast time. At a conference for Ag writers at College Park, Maryland, I scanned the menu in the stainless steel diner.

“Mr. Howard,” I asked. “Did you see any grits?”

“No grits,” my boss smiled. “Get hash browns. They’re the closest thing they have.”

He pointed to another diner’s plate, piled up with potatoes cut up for potato salad, but hijacked and sizzled in a frying pan. From the looks of the plate, that diner had squirted on a lot of ketchup. I followed his lead and found the hash browns to taste good, sort of like short fat French fries for breakfast. But I still missed the grits.

The Master said it wasn’t what you put in your mouth that defiled you, it was what came out. I have found that to be true, even in ways He may not have intended. The words of my mouth were as despicable to those in the Old Line State as they had been to the New York Yankee in Phillips Hall.

“I can’t understand you,” the guy at the gas pump said. “Your accent’s thick as mud.”

I tried again.

“I WAW nuh DAHL ahz’ WUH tha GAE ees , AEN uh KWAWT uh AW uhl,” I said slowly, so the attendant could understand. He didn’t, so Mr. Howard, who had been north before, arranged for us to get the four gallons of gas and the quart of oil .

“Why don’t you learn to talk?” the attendant said, as he took Mr. Howard’s Clemson charge card. “Where’d you come from anyway?” he asked as he brought the card back.

“I live in Klimpsun now,” I told him, “but I grew up in Poketon.”

“Poketon?”

“Yes, Poketon,” I said. “P-o-l-k-t-o-n …Poketon.”

He slapped his leg, and laughed. “You grits slay me,” he said. “Learn to talk.”

I had already tried that while I was in high school, when I enrolled in a Saturday course at the Carolina School of Broadcasting, hoping to become a radio D.J.

“Disc jockeys don’t have Southern dialects,” our teacher said. “They use the pronunciation of Middle-American speech.”

He said that I could change my speech if I used awareness, ability and habit. I was aware of the sound I wanted to make; it was the sound I was already able to use in “bite” and “night.” Now I just had to make it a habit in words like “five” and “guy,” and the pronoun “I.” So I started with the sound in “five” and added an “EE.” So my new pronunciation became “FAI eev.” I practiced and practiced, afraid I would slip out of my new dialect in class.

I was well on the way to making my new dialect a habit, when I tried it out on one of my older buddies at the Shirt Factory, where I worked after school. I was pushing a cartload of just-packed shirt boxes.

“What you got on the cart, Leon?” he asked.

I stopped and read the label on one of the green boxes.

“FAH eev twelve,” I said.

“What’d you say?”

“FAH eev twelve” I repeated.

“FAH eev twelve?”

I nodded.

“FAH eev twelve?” he said in his best Ralph Cramden voice. “FAH eev twelve? “ He paused. “What’s this blanking FAH eev twelve blank?” He came closer.

“Listen here,” he said. “Old Perch went up to New York for a week, and he came back talking like a Yankee for a month. He sounded like a bad copy of a Yankee. Do you wanta be like Perch?”

“No, I don’t want to be like Perch,” I said to myself after Benny left, even though I ‘d never even seen Perch. But I wasn’t sure why.

I dropped out of the School of Broadcasting, and never said “FAH eev” again. From then, on every time I made the sound after “H,” it was the Southern one.

But when I went off to college, I got more pressure to give up the drawl. My dialect reduction instructor, Dr. Wilson, saw that I could enunciate clearly, and that I could make the standard Middle-American “AI” sound when I wanted to, I just had not made them a habit. There was a reason for my inaction. Like other committed Southerners, I appreciated history, believing, with Santayana, that the past is priceless, that those who ignore it are forced to learn its lessons for themselves. And being a Southerner, I deeply valued the folks who went before me.

So, I made a conscious decision to keep the speech I learned at home — not because I had to, but because I felt honored to. And although it was by accident I grew up in the South, it is not by accident that my speech intentionally reveals the fact.

What to do about our accent? Keep it, preserve it, honor it. Long live the way all of us say our words: the banjo player in the city, the math whiz in the classroom, the attendant at the gas station, and this writer at the keyboard. Our dialect, our accent, the way we pronounce our words binds us to the place from which we came, so that our words become a badge of honor to those who gave them to us. Even if folks say we talk funny.

May it be forever so.

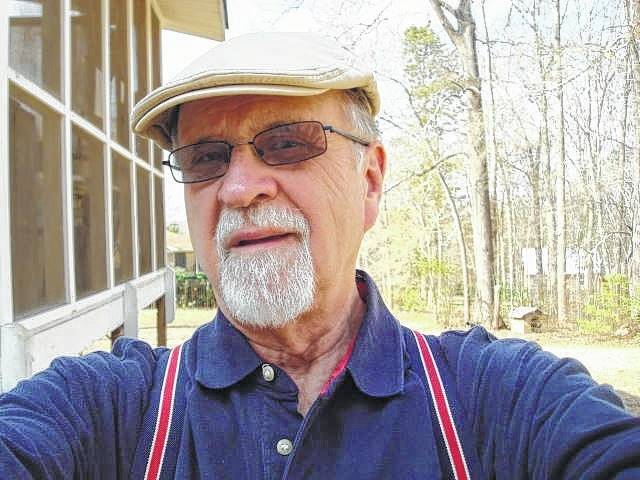

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.