The best name calling I ever took was “Close, Mr. Smith, but you never hit the mark,” as I read the upside down D+ on my English paper. My teacher, Mr. Wilson, did not use marks or words recklessly. Even when he was upset, the worst he ever said was “Merciful Heavens.” Although Mr. Wilson had the power to assign a low grade to my essay, he was too noble to offer a slur and run. So he pointed out the need for a thesis sentence to give order to my argument. And when he said “You come close…but you never hit the mark,” his smile and the quiet dignity in his voice showed me he intended no harm.

“Would you like to say something?” he asked.

“No sir,” I said, and took my paper. “Thank you, sir.”

I walked away confused about the word “never.” Nervously whistling “T for Texas,” as I walked across the quad, I warbled the third line to prove that I could hit the mark at one thing at least. But then I realized Mr. Wilson had hit the mark as well. After that day, his words pushed me to make myself more perceptive, so that I could learn the difference between things that matter and things which don’t. I could have called him “Merciful Heavens,” but I did not, because he had no intent to hurt me, and I saved my insults for attackers.

“Bud” was offered by a 200-pound, 15-year-old, as he lazed in front of the concession stand at the old Ansonia Theatre. Looking down on me, as I offered him my ticket, he intimidated me with his size and self-assurance.

“No,” he said as he held his hand up. “I don’t rip tickets. You rip tickets. So, rip it… Bud.”

I did as directed, then handed his half of the red cardboard to him.

But I did not like being ordered around and I did not like being called “Bud.” That was not my name, and the way he said it made it sound despicable. His word was half-true, an intentional put-down, punctuated by superior body language, and a haughty verbal tone. I was more than a “Bud,” and to be called so was to be hurt.

So, after noting the poorly disguised goobs splotching his forehead and cheek , I deemed him the Clearasil Cowboy, as I walked on into the theatre to watch Cisco and Pancho.

“You dummy” was offered lightly, but was not received that way, because of the mood I was in — the worst “I’m gonna eat a worm” funk I had ever known.

“You left page 3 out of your report,” Ray said. Then he paused before he chuckled and said, “What did you do that for, you dummy.”

Ray had never said one unkind word to me. But these two words hurt me as as bad as any I had ever heard. When we hung up, I sent him the missing information, then got in my little car, and drove out into the country, hearing “you dummy” over and over again. After a while, the hurt turned to anger, and the anger turned to action as I kicked the accelerator to the floorboard, pushing it so hard and so long that the gearshift began to knock. I pulled over and got out to listen. “That dumb Yankee caused me a lot of trouble,” I said. The trouble part turned out to be true, the blame totally untrue, my name for Ray, only half so.

”You…yeah you,” a teenager called, squatting with the other nicotiners in front of the Ag building as he exhaled smoke from a Camel. Two or three years older, taller by at least six inches, and heavier by 65 pounds, he amplified his opinion with the words, “I don’t like your looks.” His words startled me, because I could see no reason for him to dislike my looks. “Dromedary breath” came to me as I passed on by. But my words were only a partial truth; he was more than a kid who had tinctured his breath with Camel smoke. I could not help how I looked, and neither could he. But I did not realize at the time spoken contempt for another person’s being can hurt the caller as much as the callee.

“You always were a smart-aleck,” the woman said, as she got in her car and slammed the door. I did not return the insult because she was 20 years my senior and knew my parents. But I did tell myself this angry woman “must have got ahold of some bad Alpo.” I may have been a smart aleck, but there was falsehood in the “always.” As an infant, I could not even speak. As a younger man, I could sometimes make a discerning comeback, but only when sorely pushed. But the Alpo line was a half-truth, too, for I had seen times when my attacker had been kind and, from time to time, even charming. But here, her words were intended to hurt, and they accomplished their purpose.

Another all-encompassing slur, “I hate your guts,” was offered me by an older boy, who repeatedly tried to get me to go outside the lunch room to fight. But I ignored his requests, seeing safety in the numbers, who stood on either side of us in the lunch line.

I had mouthed back at him before, and would have said if he were dressed out, he would lose 170 pounds, and that his ample innards didn’t smell like tube roses either. But I held my peace because he was really angry, and this time he said what he had only hinted before: he hated me. Words of authentic hate are scary. Sometimes they are not quite so obvious.

The archetypical example comes from the angel called “son of the morning” who tried to storm Heaven and occupy the throne of God. When he lost the battle, he was thrown out and found himself on Earth. Angry at his plight, the evil one decided to trick the humans into disobeying God, knowing they would suffer for doing so. He disguised himself as a serpent before approaching Eve, and began his attack with the words “Hath god said…?” He used the lower case word for a reason.

Eve knew God by two names: Yahweh Elohim, the self-existent god. The evil one used the second half of the divine name by itself to cut God down to size, so Eve could act in his own best interest, and die as a result.

Name calling to do harm is evil. And so were the hurtful names I used in this article: Dumb Yankee; Clearasil Kid; Dromedary Breath; Bad Alpo; Dressed out would lose 170 pounds. I might rationalize using these names by saying, “They bought every bit of that.” But as I take Mr. Wilson’s lesson to heart, I realize that to use such words is to do the work of the evil one, and in that kind of relationship the humans always lose, and sometimes die.

Take Ty for example. Ty was 9-year-old boy in Oklahoma, not only small for his age, but also carrying the surname name “Smalley.” He had been happy-go-lucky until the third grade, when the other kids began to call him by his last name, while emphasizing the first syllable. After deriding his family name, they began to taunt him with others, like “TY-ny Tim” and “Shrimp,” adding all the disdain and contempt third-graders could muster. Ty never said or did anything in return.

The hurtful names morphed into physical attacks. He told his mother why he hated to go to school. She worked there and repeatedly begged for someone to do something. But the physical attacks continued, such as the one which ended with Ty shoved into a hallway locker, and that which ended with his being crammed into a garbage can, face-first.

Finally cornered in the gym, little Ty fought back, but received a three-day suspension for defending himself. His adversary got only one day and was already back in school when Ty Smalley ended his 10-year-old life. The game that started with name-calling ended in Ty’s death. Those who assisted in his killing are bound to suffer, too.

So cruel names strike both ways. Our words may ridicule others, but each time we use them, something good inside us dies. The sticks and stones I cast may not hurt me, but the harsh and cruel words I speak will hurt others, and sooner or later they will return to hurt me.

With divine help, I am giving them up.

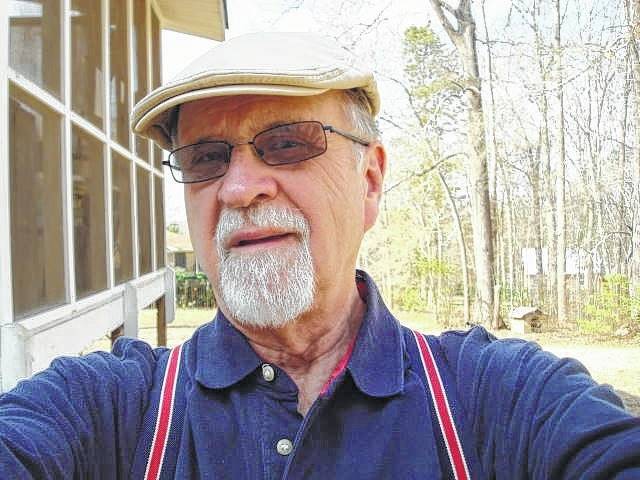

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.