Marty Glickman (left) and Sam Stoller were supposed to compete in the 400-meter relay but were denied because of antisemitism.

Contributed photo

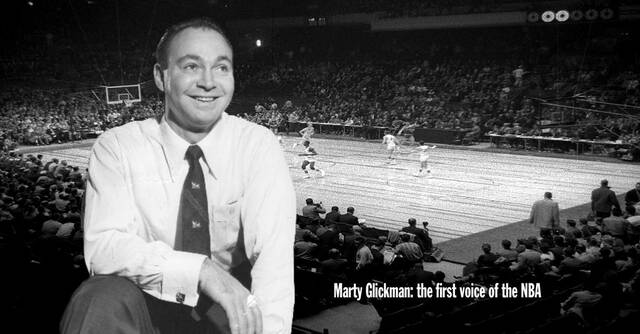

CHARLOTTE — I watched this year’s Charlotte Jewish Film Festival virtual screening of “Glickman” which tells the story of Marty Glickman who was supposed to be an Olympics medalist, but was turned away because of antisemitism — and how he vowed to never let that happen to anyone ever again.

Glickman was a football player, basketball player, and sprinter while in high school and at Syracuse University. He was regarded as the “fastest kid on the block,” and the third-fastest person in the world. He qualified in track and field for the 1936 Olympics that took place in Nazi Germany.

Glickman and Sam Stoller were the only Jews on the American team. But the day before they were supposed to compete in the 400-meter relay, coaches called them into an unscheduled meeting and told them Germany was allegedly hiding secret sprinters to cause an upset, and Glickman and Stoller would need to be replaced by Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe. Owens, who had already won three medals, tried to step down but the coaches wouldn’t let him.

The decision didn’t add up. Glickman and Stoller were the predicted frontrunners for the relay, expected to win by at least fifteen yards. Glickman had also beaten the best German sprinter in a world competition prior to the Olympics. Then the results came in. The American team won by a landslide, and Germany had no secret sprinters — they finished well behind the rest of the competition.

What Glickman, other sprinters, and future Olympics officials believed was that the coaches and head U.S. Olympics staff were Nazi sympathizers who tried to appease Adolf Hitler. Hitler wanted to use the Olympics as proof of Aryan supremacy, and he had already been humiliated by the black American team member, Owens, winning gold. It would be even worse if he saw two Jews on the podium.

“In the entire history of the modern Olympic Games, no fit American track and field performer has ever not competed in the Olympic Games except for Sam Stoller and me — the only 2 Jews on the 1936 team,” Glickman later said in an interview. “Watching the final the following day, I [saw] Metcalfe passing runners down the backstretch, he ran the second leg, and [I thought] that should be me out there. That should be me. That’s me out there.”

Many years later in 1998 to try and make amends, head Olympics officials gave Glickman, and posthumously Stoller, two plaques in lieu of the gold medals they should have won.

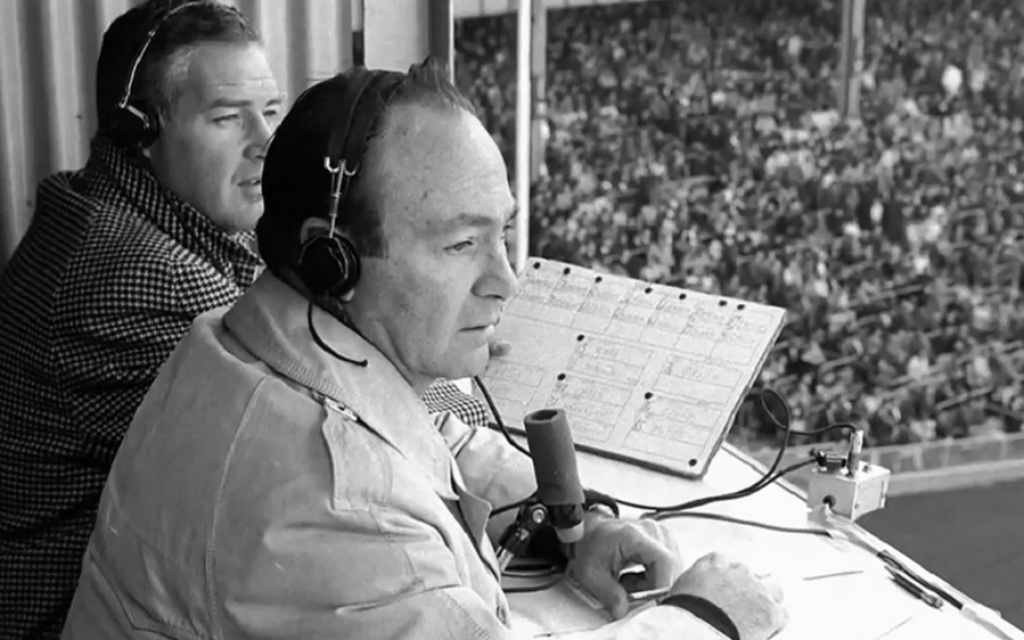

Following the Olympics, Glickman enlisted in the Marines and fought in WWII in the Central Pacific. After the war, he became a famous sports broadcaster on the radio for a variety of college and high school sports. He hosted a late-night radio show, brokered the first NBA deal, narrated play-by-plays and Paramount Newsreels, narrated Yonkers’ horse races, and even broadcasted for the Knicks and Giants at their peak.

Glickman was known particularly for his basketball broadcasting where he would coin new terms still used in basketball today like “swish.”

He invented the sports style and vernacular in broadcasting, changing the way people talked about the game and laying out the geography of the court and field. According to the film, he elevated sports and changed the landscape of sports and broadcasting, “embedding the games in the consciousness of American minds.”

“No one framed the basketball games like Glickman did. It was like television on the radio. He made it so people knew about basketball without being there and painted it in your mind,” celebrity Larry King said in archived footage.

Glickman also cared about New York City and its people, mentoring both athletes and future sports broadcasters. He notably helped many children and spoke about his Olympics experience at Jewish conferences focused on fighting antisemitism.

Glickman passed away in 2001. He left behind a legacy of squashed Olympics dreams but rose to become one of the best sports broadcasters in history, defining the profession for years to come.

“Glickman” is an amazing documentary that takes a look back at how Glickman made history and how he showed Judaism could persist. The documentary features narration intertwined with footage from broadcasted games and the Olympics, plus Glickman’s archived interviews, and famous celebrities talking about his legacy. “Glickman” first premiered on HBO in 2013 and has been revived in this year’s collection of Jewish films at the Charlotte Jewish Film Festival. It now can be found on Apple TV.

To support the Anson Record call 704-994-5474 or visit https://ansonrecord.com/subscribe.

Reach Hannah Barron at 704-994-5471 or hbarron@ansonrecord.com.